Summary and Analysis of Cullinan’s If Nature had Rights & Ken Burns’ American Buffalo

The oppression of a people is inextricable from the oppression and subjugation of nature. Colonisers have always used the strategy of attacking nature to weaken a native population. I will be examining the ways this was conducted against Native Americans, as well as looking at how cultural mysticism leads to reverence of nature juxtaposed against Western science and the commodification of it. For the purposes of the analysis, I want to look particularly at American Buffalo and Cullinan’s If Nature had Rights.

Cullinan in If Nature had Rights attempts to equate the destruction of nature and the stripping of its rights (as could be seen with the Native cultures and the upholding of nature’s rights) to become a commodity, to the slavery and dehumanization of Black people in the US, which I find to be an egregious and inequitable comparison. Nature’s rights are undoubtedly important, but human rights are more so due to the fact of sapience; in American Buffalo, the act of skinning and making coats of buffalo hide isn’t the egregious part of the history, but the crime lies in the scale it was conducted at. However, if we apply this idea to Black people in Jim Crow US, their skin was used to make shoes, wallets, cigar cases and more (Jim Crow Museum), and I would argue that the latter is significantly more heinous. This example illustrates that the oppression of people and nature cannot be equated to the same moral depravity, though they are interlinked in many ways.

Culture and nature are synonymous, all culture is derived from their surroundings. Looking at American Buffalo, one of the first things said is: “the buffalos were the life of the Kiowas”, thereby emphasizing immediately that the culture was tired to the buffalo, a part of the natural world, likewise, the Kiowa and other Native American tribes see themselves as a part of nature, and as we’ll see further into this analysis. The documentary covers topics of American Settlers colonising the continent, and the way in which their presence shifts the culture of the Natives, and the documentary juxtaposes the treatment of the buffalo by Natives with that of the settlers, and the industrial capitalistic systems of insatiable demand for buffalo coats they brought with them.

The slaughter of the buffalo, however, was not solely driven but the demand for coats and the sport of the hunt. It was an intentional way of breaking the spirit of the Native tribes, “They understood the obvious, that the bison were the key to the Native economy, if you cut the legs from under the economy then you weren’t going to have much resistance from the native people” (American Buffalo, 1:11:46). They knew that removing the foundation of the Native economy would increase their reliance on the US government for food and the survival of their people. This extermination of the buffalo impacted the Native tribes deeply, “We had the songs but no buffalo to sing them to, it was spiritual trauma” (American Buffalo, 1:45:0).

The Kiowa saw the buffalo as integral to many aspects of their culture and spiritual practices, for example they used buffalo heads as masks during such practices. The culture emphasized buffalo as a creature to be respected, they were taught that the buffalo was sacred and needed to be treated as such before they were taught of all the ways their society benefitted from the parts of the buffalo; hereby highlighting how the mystification of buffalo as a sacred being places it in a position of respect. When they killed a buffalo, they utilised all its constituents, from the horns for arrowheads and spears, and fed communities with all of the hundreds of pounds of meat; Gerard Baker in the documentary says, “Even the waste wasn’t wasted” (American Buffalo, 19:47), furthermore, they utilised the sounds of the buffalo in their hunting practices, which I would describe as harmonious with nature. The buffalo was thereby the legs that supported the weight of Native populations, providing them with tools, food, clothing, and invigorating their cultural practices. The Natives had other hunting practices that made use of animals, they’d shroud themselves in cowls of other animals to encroach on the buffalo unnoticed; they would effectively become one with nature. This relationship with nature was symbiotic, they took what they needed and gave back to nature, and treated it with reverence, this is an incredibly stark contrast to the way the colonisers treated it when their ships docked on the beaches.

For the settlers, the buffalo was seen only for the benefits it could provide them, and the land was a resource intended for their exploitation. Their literal presence spread plagues among the indigenous populations, which I suppose could be morbid symbolism. The American landscape was teeming with Buffalo from Floride to Lake Erie (American Buffalo, 25:46), but by the end of their slaughter, there were only a handful left. The way the buffalo were used for their resources was far more perverse than the way the natives went about it, “they left 600 to 800 pounds of meat, along with the hooves and the head and the horns to rot” (American Buffalo, 1:07:16), and even then the hides were wasted because the production line meant that many of the hides were not usable for coats (American Buffalo, 1:09:30).

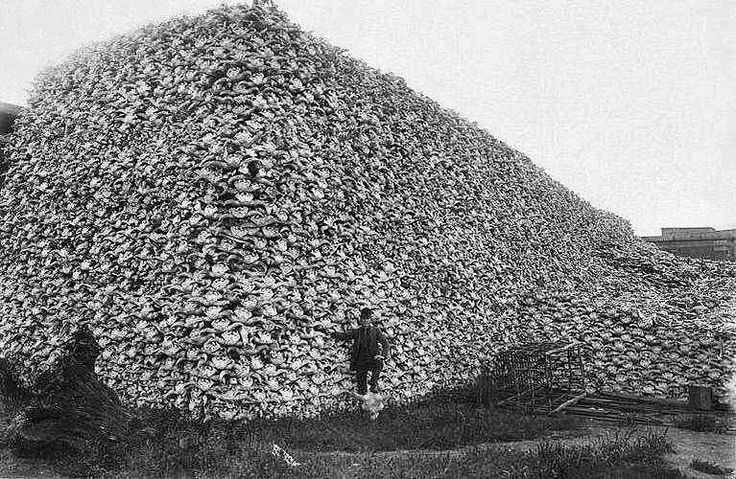

They were wasteful to the nth degree with the resources of the buffalo, where the natives ensured to use every part of the buffalo to nurture their communities, the colonisers slaughter the buffalo, took only the parts they needed to sell off in other parts of the country, and left all the rest of it to rot in the field. All the parts of the buffalo were not given the same (albeit still minimal) respect as was given to the hides because it was only those that were to beg a profit and were seen as valuable, the sacrifice of the animal disregarded. Near the end of the bison runner lifecycle, they came back to beat a dead horse (or bison,I suppose) and used the leftover skulls to make even more profit. No other image encapsulates the cold industrialisation more than the men standing before the mountain of buffalo

posing and proud to be the harbinger of its near extinction. The hunting methods were also perverse, the use of guns killed bison at never-before-seen numbers, it was even gamified as a shooting expedition when the rails were laid for trains, furthermore they abused a product of evolution in their slaughter, illustrating their disregard for nature perfectly. All of this, the consumerist drive for buffalo coats, the production of bigger and better firearms to kill buffalo more effectively, and the gamification of it, all shows this cold commodification of the buffalo. The Kiowa and other Native tribes evolved alongside the buffalo for 10,000 years, and it only took a few hundred of coloniser hunting to eradicate their population.

The subjugation of nature and its peoples are one in the same, and in crushing the mysticism of nature in favour of colonial capitalistic commodification, they can generate profits. Killing the buffalo made the Natives more dependent on the US Government for food, clothing, etc, and thereby was backed into a corner and controlled by the government to smother the flame of their culture. In destroying nature, the settlers destroyed the Natives.

References

Human leather – April 2013. Jim Crow Museum. The Mercury. (n.d.). https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/question/2013/april.htm

Cullinan, C. (2008, January 1). If Nature Had Rights. Orion Magazine. https://orionmagazine.org/article/if-nature-had-rights/

Burns, K. (2023, October). The American buffalo. PBS.

https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-american-buffalo#watch